By November 1978, Dylan had received some of the worst reviews of his career. In late January, he finally premiered Renaldo and Clara, the part-fiction, part-concert film shot in the fall of 1975, during the first Rolling Thunder Revue tour. Though the performances were well-received, the overwhelming majority of reviews were negative. A number of them were so harsh, Dylan saw them as personal attacks, particularly those by The Village Voice, which printed four negative reviews by four different critics.

In the meantime, Dylan's latest tour was getting its own share of negative reviews, many of which reflected the negative criticism waiting to greet the American release of Bob Dylan at Budokan, taken from performances held in early 1978.

Yet Dylan was in good spirits, according to his own account. "I was doing fine. I had come a long way in just the year we were on the road [in 1978]." This would change on November 17th in San Diego, California. As Clinton Heylin reports, "the show itself was proving to be very physically demanding, but then, he perhaps reasoned, he'd played a gig in Montreal a month earlier with a temperature of 105."

"Towards the end of the show someone out in the crowd...knew I wasn't feeling too well," recalled Dylan in a 1979 interview. "I think they could see that. And they threw a silver cross on the stage. Now usually I don't pick things up in front of the stage. Once in a while I do. Sometimes I don't. But I looked down at that cross. I said, 'I gotta pick that up.' So I picked up the cross and I put it in my pocket...And I brought it backstage and I brought it with me to the next town, which was out in Arizona...I was feeling even worse than I'd felt when I was in San Diego. I said, 'Well, I need something tonight.' I didn't know what it was. I was used to all kinds of things. I said, 'I need something tonight that I didn't have before.' And I looked in my pocket and I had this cross."

|

| Dylan performing in Rotterdam, June 23, 1978 One year before his conversion. |

Heylin writes that "his state of mind may well have made him susceptible to such an experience. Lacking a sense of purpose in his personal life since the collapse of his marriage, he came to believe that, when Jesus revealed Himself, He quite literally rescued him from an early grave."

"[Dylan's] conversion wasn't one of those things that happens when an alcoholic goes to Alcoholics Anonymous," David Mansfield, one of Dylan's band members and fellow-born-again Christian, would later say. "The simplest explanation is that he had a very profound experience which answered certain lifelong issues for him."

Hints of Dylan's newfound faith began to appear publicly. In the final four weeks of the tour, Dylan could be seen wearing the same silver cross that catalyzed his conversion. During performances of "Tangled Up in Blue," lyrics were replaced with explicit references to the Bible. As Heylin writes, "Rather than having the mysterious lady in the topless bar quoting an Italian poet from the 14th century [sic], she was quoting from the Bible, initially from the Gospel According to Matthew. Gradually, though, the lines changed, until he settled upon a verse from Jeremiah - the one he would quote on the inner sleeve of the Saved album: 'Behold, the days come, sayeth the Lord, that I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel, and with the house of Judah' (Jeremiah 31:31)."

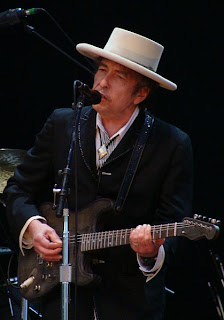

|

| Dylan in Toronto April 18, 1980, after his conversion |

Dylan wasn't alone in his religious awakening. Band members Steven Soles and David Mansfield had already joined the Vineyard Fellowship, a Christian organization introduced to them by T-Bone Burnett. Helena Springs, one of the singers in the band, was brought up Christian and still practiced her faith. Dylan was also romantically linked with Mary Alice Artes; raised as a Christian, she had strayed from her faith only to return to it after joining the Vineyard Fellowship (without the influence of Burnett, Soles, or Mansfield).

At one meeting with the Vineyard Fellowship, Artes approached pastor Kenn Gulliksen, seeking pastoral guidance for Dylan. Pastors Larry Myers and Paul Esmond were sent to Dylan's home where they ministered to him. As Heylin writes, "by embracing the brand of Christianity advocated by the Vineyard Fellowship, Dylan was about to become, in popular perception, just another Bible-[thumping] fundamentalist. In fact, though the Fellowship certainly shared the 'born again' precepts of more right-wing credos - believing such a change was an awakening from original sin ('Adam given the Devil reign/Because he sinned I got no choice') - it represented a more joyous baptism of faith." As Mansfield would say, "a big part of the fellowship of that church was music."

Under the guidance of the Vineyard Fellowship, Dylan was asked to attend a course held at the Vineyard School of Discipleship, which would run four days a week over the course of three months. "At first I said, 'There's no way I can devote three months to this,'" Dylan would say in a 1980 interview. "'I've got to be back on the road soon.' But I was sleeping one day and I just sat up in bed at seven in the morning and I was compelled to get dressed and drive over to the Bible school."

Pastor Gulliksen would later say, "It was an intensive course studying about the life of Jesus; principles of discipleship; the Sermon on the Mount; what it is to be a believer; how to grow; how to share...but at the same time a good solid Bible-study overview type of ministry."

As Heylin writes, "A well-read man, for whom the Bible had previously been little more than a literary source, [Dylan] now made its allegories come out in black and white." In an interview taken in 1985, Dylan would say, "What I learned in Bible school was just...an extension of the same thing I believed in all along, but just couldn't verbalize or articulate...People who believe in the coming of the Messiah live their lives right now, as if He was here. That's my idea of it, anyway. I know people are going to say to themselves, 'What the fuck is this guy talking about?' but it's all there in black and white, the written and unwritten word. I don't have to defend this. The scriptures back me up."

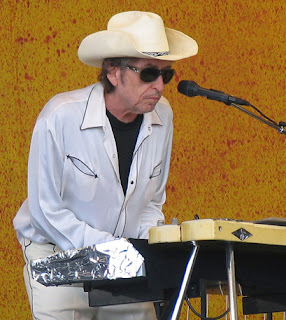

|

| On keyboards at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, April 28, 2006 |

"According to Lindsey, current world events had been foretold in the apocalyptic tracts of the Bible," Heylin continued. "His basic premise, in The Late Great Planet Earth, was that the events revealed to St. John in Revelation corresponded with 20th century history, starting with the re-establishment of the Jews' homeland, Israel. By identifying Russia as Magog and Iran as Gog - the confederation responsible for instigating the final conflict, the Battle of Armageddon - Lindsey prophesied an imminent End."

In later shows, Dylan would reflect these beliefs on stage. At one show in the fall of 1979, Dylan said, "You know we're living in the end times...The scriptures say, 'In the last days, perilous times shall be at hand. Men shall become lovers of their own selves. Blasphemous, heavy and highminded.'...Take a look at the Middle East. We're heading for a war...I told you 'The Times They Are A-Changin' ' and they did. I said the answer was 'Blowin' in the Wind' and it was. I'm telling you now Jesus is coming back, and He is! And there is no other way of salvation...Jesus is coming back to set up His kingdom in Jerusalem for a thousand years."

As Heylin writes, "[Dylan's] belief in the imminence of the End was reflected in almost all of the songs he now found himself writing." Dylan would later say in an interview taken in 1984, "The songs that I wrote for the Slow Train album [frightened me]...I didn't plan to write them...I didn't like writing them. I didn't want to write them."

"Precious Angel," "Gonna Change My Way of Thinking," "When You Gonna Wake Up?" and "When He Returns" all "drew heavily and directly upon the Book of Revelation," notes Heylin. "In the early months of 1979, Dylan was writing his most message-driven album in sixteen years. This time, though, the pursuit of the millennium had overtaken more sociopolitical concerns."

THE RECORDING SESSIONS

Dylan also approached Jerry Wexler to produce the upcoming sessions. Studio recording had become much more complex during the 1970s, and after his struggles recording the large ensemble performances of Street-Legal, Dylan was resolute in hiring an experienced producer he could trust. He was familiar with Wexler's celebrated work with Aretha Franklin, Wilson Pickett, Percy Sledge, Dusty Springfield, and other soul artists. "Synonymous with a small studio in Sheffield, Alabama, the sixties Atlantic recordings of Wexler defined the Muscle Shoals Sound," writes Clinton Heylin. Like Knopfler, when Wexler agreed to produce, he was unaware of the nature of the material that awaited him.

"Naturally, I wanted to do the album in Muscle Shoals - as Bob did - but we decided to prep it in L.A., where Bob lived," recalls Wexler. "That's when I learned what the songs were about: born-again Christians in the old corral...I liked the irony of Bob coming to me, the Wandering Jew, to get the Jesus feel...[But] I had no idea he was on this born-again Christian trip until he started to evangelize me. I said, 'Bob, you're dealing with a sixty-two-year-old confirmed Jewish atheist. I'm hopeless. Let's just make an album.'"

Knopfler voiced his concerns to his manager, Ed Bicknell, remarking that "all these songs are about God," but he was also impressed with Dylan's professionalism. "Bob and I ran down a lot of those songs beforehand," recalls Knopfler. "And they might be in a very different form when he's just hittin' the piano, and maybe I'd make suggestions about the tempo or whatever. Or I'd say, 'What about a twelve-string?'"

When sessions were held in Alabama, Dylan retained only two members from his 1978 touring band: Helena Springs and Carolyn Dennis, both background singers. Veteran bassist Tim Drummond was hired, as was Dire Straits' drummer Pick Withers on Knopfler's recommendation. Keyboardist Barry Beckett and the famous Muscle Shoals Horns, all key elements of the celebrated Muscle Shoals Sound, were also brought in.

|

| Dylan, the Spectrum, 2007 |

"Bob began playing and singing along with the musicians," recalls Wexler. "We were in the first stages of building rhythm arrangements; it was too soon for him to sing, but he sang on every take anyway. I finally persuaded him to hold off on the vocals until later, when the arrangements were in shape and the players could place their licks around - not against - Bob."

As the sessions wore on, Wexler's techniques seemed more accommodating. Once arrangements were set, Dylan could focus on recording a strong vocal track while subsequent overdubs would fill in the gaps. As Heylin describes it, the basic tracks with "lead vocals intact [were] laid down before Dylan's boredom threshold was reached. Adding and redoing bass parts, acoustic and electric guitars, background vocals, horns, organ, electric piano, and percussion would require their own set of sessions, but by then Dylan could be an interested observer." For "Precious Angel," bass, guitar, organ, and horns would all be overdubbed a week after recording the master take. "No Man Righteous (Not No One)" (ultimately left off Slow Train Coming) was also constructed in similar fashion.

The final song recorded was "When He Returns." Its role as the album's closer was already decided, but Dylan planned on having Springs or Dennis sing the lead vocal. After recording a guide vocal, backed by Beckett on piano, he reconsidered. As Heylin suggested, Beckett's "strident accompaniment made him think again." Dylan practiced singing "When He Returns" overnight before laying down eight vocal takes over Beckett's original piano track. The final take, described by Heylin as "perhaps Dylan's strongest studio vocal since 'Visions of Johanna'," was selected as the master.

Wexler convinced Dylan to overdub new vocals for "Gonna Change My Way Of Thinking" and "When You Gonna Wake Up?", but otherwise the overdubbing sessions held the following week focused on instrumental overdubbing.

RECEPTION AND AFTERMATH

Before the album was completed, Patty Valentine had brought a defamation-of-character suit against Dylan, regarding the song "Hurricane" from Desire; on May 22, while giving a pre-trial deposition in his defense, Dylan was asked about his wealth. "You mean my treasure on earth?" replied Dylan. He was asked about the identity of the 'fool' in "Hurricane." Dylan said the 'fool' was "whoever Satan gave power to...whoever was blind to the truth and was living by his own truth." Five days later, Dylan's pre-trial statement was reported in The Washington Post, which also interviewed Kenn Gulliksen, who revealed to the paper that Dylan had joined the Vineyard Christian Fellowship.

By June, with the album virtually finished, Dylan gave London's Capital Radio station an acetate of "Precious Angel," which premiered on Roger Scott's afternoon radio show. By July, the album was ready for issue, and pre-release copies of Slow Train Coming circulated through the press. New Musical Express would proclaim "Dylan & God - It's Official."

In a year when Van Morrison and Patti Smith released their own spiritual works in Into the Music and Wave, respectively, Dylan's album seemed vitriolic and bitter in comparison. Critic Charles Shaar Murray wrote, "Bob Dylan has never seemed more perfect and more impressive than on this album. He has also never seemed more unpleasant and hate-filled." Greil Marcus wrote, "Dylan's received truths never threaten the unbeliever, they only chill the soul" and accused Dylan of "sell[ing] a prepackaged doctrine he's received from someone else." According to Clinton Heylin, "Marcus isolated Slow Train Coming's greatest flaw, an inevitable by-product of his determination to capture the immediacy of newfound faith in song."

On October 18, 1979, Dylan promoted the album with his first—and, to date, only—appearance on Saturday Night Live, performing "Gotta Serve Somebody," "I Believe In You," and "When You Gonna Wake Up." Nearly two weeks later, on November 1, Dylan began a lengthy residency at the Fox Warfield Theater in San Francisco, California, playing a total of fourteen dates supported by a large ensemble. It was the beginning of six months of touring North America, performing his new music to believers and his heckling fans alike.

Despite the mixed reactions to Dylan's new direction, "Gotta Serve Somebody" was a U.S. Top 30 hit, and the album outsold both Blood on the Tracks and Blonde on Blonde in its first year of release, despite missing the top of the charts. It even managed to place at #38 on The Village Voice's Pazz & Jop Critics Poll for 1979, proving he had some critical support if not universal acclaim.

In the meantime, Dylan refused to play any of his older compositions, as well as any secular material. Though Larry Myers had assured Dylan that his old compositions were not sacrilegious, Dylan would say he would not "sing any song which hasn't been given to me by the Lord to sing." Fans wishing to hear his older songs openly expressed their disappointment. Hecklers continued to appear at his concerts, only to be answered by lectures from the stage.

Dylan was firmly entrenched in his evangelical ways, and it would continue through his next album, whether his audience would follow or not.

----------

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slow_Train_Coming

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bob_Dylan

http://images.wax.fm/bob_dylan_slow_train_coming-CBS32524-1271882965.jpeg

http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/images/episode/b00pdhzs_640_360.jpg

http://sexedmusic.files.wordpress.com/2009/10/bob-dylan.jpg

http://www.robertstadium.com/images/BobDylan.jpg

http://today.ucf.edu/files/2010/09/dylan_pic_8.jpg

No comments:

Post a Comment